“A Bungalow, a Piccolo, and You!” Words and music by Al Lewis, Al Sherman, and Lee David (1932). Recorded in London at Studio 1, Abbey Road on July 22, 1932 by Ambrose and His Orchestra with vocalists Sam Browne and Elsie Carlisle. HMV B-6218 mx. 0B-2378-1.

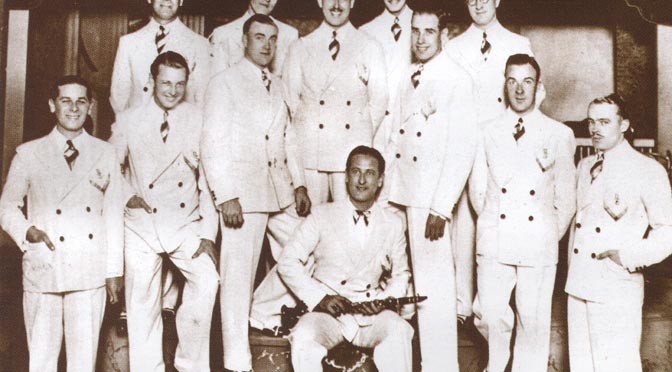

Personnel: Bert Ambrose dir. Max Goldberg-Harry Owen-t / Ted Heath-tb / Joe Crossman-cl-as-bar / Billy Amstell-cl-as-ts / Harry Hines-as / Joe Jeanette-cl-ts-?pic / Ernie Lewis-Teddy Sinclair-Peter Rush-vn / Bert Read-p / Joe Brannelly-g / Don Stutely-sb / Max Bacon-d1

A Bungalow, a Piccolo, and You ! – Ambrose and his Orchestra

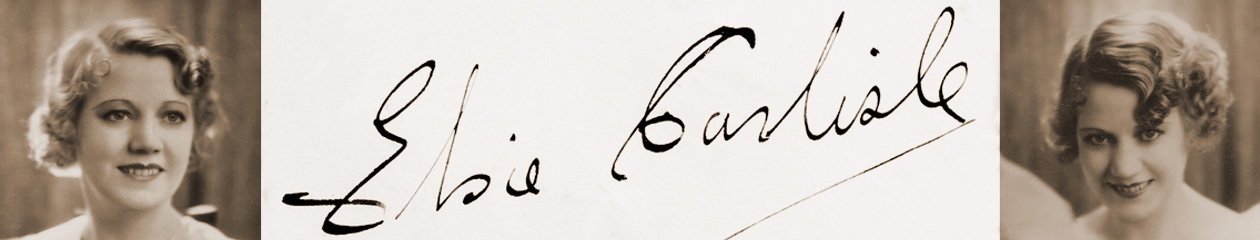

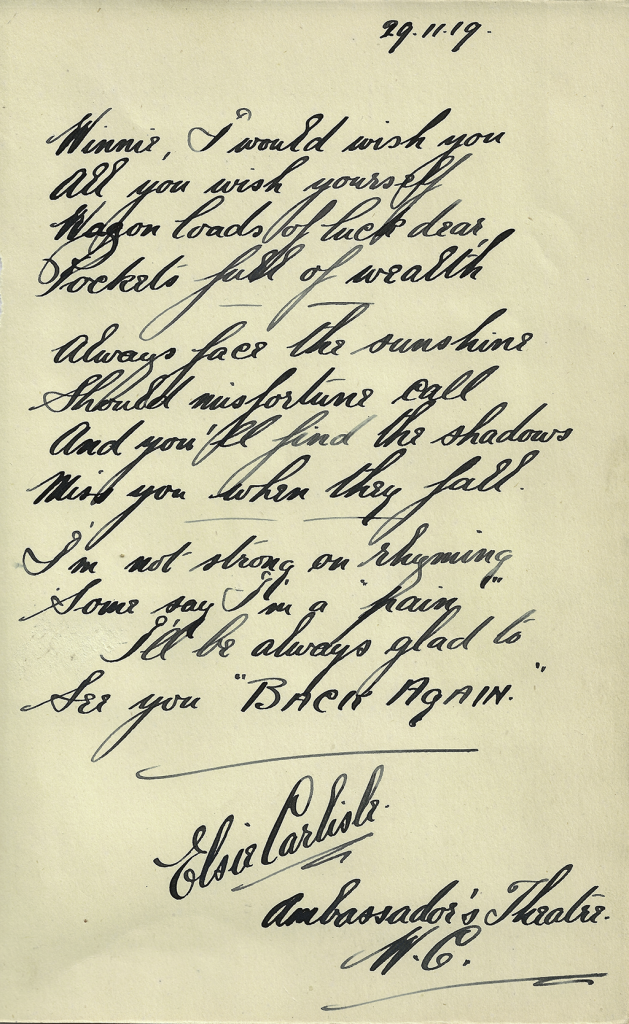

The Elsie Carlisle vocal in “A Bungalow, a Piccolo, and You!” has often been overlooked. Edward Walker mentioned it in his 1974 discography, but the attribution was omitted by Rust and Forbes, Johnson, and Laird,2 and even by the first edition of my own Croonette: An Elsie Carlisle Discography, though that oversight has since been remedied.

The songwriters include Al Sherman and Al Lewis, who would later collaborate on “No! No! A Thousand Times No!” and Lee David, who would team up with Darl MacBoyle to write “That Means You’re Falling in Love” (the latter song was recorded in 1933 by Sam Browne and Elsie Carlisle). The 1932 “A Bungalow, a Piccolo, and You!” looks backward to songs with such titles as “A Bungalow, a Radio, and You” (Dempsey-Liebert; 1928) and “A Cup of Coffee, a Sandwich, and You” (Meyer-Dubin-Rose; 1925),3 though doubtless the formula being followed in all three compositions derives from a famous older phrase in Edward Fitzgerald’s various editions of his translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (“A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse—and Thou,” in the first [1859] and second [1868] editions; “A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou” in the third [1872], fourth [1879], and fifth [1889] editions), the joke being that we would not normally expect light modern love songs to compare themselves implicitly to profound medieval Persian philosophical poetry.

Ambrose’s version of the song has a mostly instrumental introduction, except that very near the beginning a piccolo plays three series of notes that Elsie can be heard to mimic vocally. The piccolo continues to intervene playfully, even comically, throughout the song. Then Sam Browne begins to sing, describing himself as standing beneath someone’s window and telling her that all he needs is a bungalow, a piccolo, “and you.” Browne’s fun but comparatively brainless vocal proceeds until the piccolo takes over for a moment. It is at that point that something incredibly cute occurs: Elsie again has an exchange with the piccolo in which she imitates it with her voice, but this time she scats. Even better, she boops (“Boop-a-doo!”), and then repeats Sam’s sentiments about needing a bungalow, a piccolo, “and you.” Overall, her contributions to the recording are brief but bright and joyful.

While the songwriters were all American, I have not been able to locate any American recordings of “A Bungalow, a Piccolo, and You!” There are plenty of other British dance band recordings, however, including those by Henry Hall’s BBC Dance Orchestra (v. Val Rosing), Billy Cotton and His Band (v. Cyril Grantham), Terence McGovern (as Terry Mack and His Boys; v. Joe Leigh), Jack Hylton and His Orchestra (v. Pat O’Malley), Jack Payne and His Band (v. Jack Payne, Bob Manning, and Charlie Asplin), Nat Star (as Billy Seymour and the Boys; v. Fred Douglas), Jay Wilbur and His Band (as Jack Grose and His Metropole Players; v. Leslie Holmes), and Lew Stone and the Monseigneur Band (in a medley).

Notes:

- These are the personnel according to Rust and Forbes’s British Dance Bands on Record; for the tentative identification of Joe Jeanette as the piccolo player, I have Nick Dellow to thank. Jeanette apparently played piccolo and flute in the British army years before joining Ambrose’s orchestra. ↩

- Edward S. Walker, Elsie Carlisle — With a Different Style: A Discography, published by the author, 1974; Brian Rust and Sandy Forbes, British Dance Bands on Record, 1911 to 1945, and Supplement, Richard Clay, Ltd., 1989; Richard J. Johnson, Elsie Carlisle: A Discography, published by the author, 1994; Ross Laird, Moanin’ Low: A Discography of Female Popular Vocal Recordings, 1920-1933, Westport, Connecticut, 1996. ↩

- My thanks to Jonathan David Holmes for reminding me of the latter tune. ↩